Tales of Hoffmann, Magic Flute provide contrast at workshop

By STEPHEN PEDERSEN

Fri, Aug 5 – 4:55 AM

Jacques Offenbach’s Tales of Hoffmann is a tale for our times. It is gothic, spooky, and scarily romantic, and although no vampires suck blood in it, men’s shadows are stolen and a sexy woman is at the heart of it.

Actually, it is not one sexy woman, but four, and their names are Stella, Olympia, Giulietta and Antonia.

And there is a hint of a fifth in the Halifax Summer Opera Workshop’s production, opening in the Dunn Theatre Friday night, an ambiguous character called Niklausse, usually sung by a woman, as it is here, but in this case, transformed by director Nina Scott-Stoddart into an actual woman with a major thing for the hero, E.T.A. Hoffmann.

“What I am doing with Niklausse, who is often used as a framing device (for the tales) is making her not just a pants role, but actually a woman,” Scott-Stoddart said in a break between rehearsals last week.

“Visually, the production is all based on steampunk, so I re-imagined Niklausse as one of the guys, a very capable person, but secretly in love with Hoffmann herself.”

It was first produced privately in 1879, but the real-life poet E.T.A. Hoffmann never saw it. He died in 1822, and Offenbach, the composer of the opera — based on several Hoffmann’s tales — failed to complete it before he too passed on.

Over a prologue, three acts, and an epilogue, the hard-drinking poet, well on the way to boozing himself insensible, entertains the patrons of a popular cafe with stories of love, first a comic tale ridiculing the dwarf Kleinzach, followed by stories of his own frustrated loves with the mechanical doll Olympia (Act 1), the courtesan Giulietta (Act 2), and the consumptive opera singer Antonia (Act 3), who must never sing or she will die, so powerful is the consuming passion of her artistry.

So much for Hoffmann’s stories of past loves. The entire opera tells the tale of his current love for the opera singer Stella. She, in case you haven’t guessed it, is the living embodiment of all his loves.

All but one, that is. His muse, who, as Niklausse, claims him for herself in the epilogue. “You belong to me, you must love only me,” she tells him. Conveniently, about this time, the poet passes not on, but out.

Scott-Stoddart recalled that “ivresse,” the French word for drunkenness, is the same as the word for inspiration. At the end, Hoffmann shows he already belongs to Niklausse as muse.

“I read all the Hoffmann stories upon which the libretto is based; they are like Edgar Allen Poe — gothic, supernatural, everybody going mad, full of violence,” Scott-Stoddart said.

“The original of Coppelius (a magician) was the Sandman. But he wouldn’t sprinkle sand in children’s eyes to make them sleep; he would come, and if they weren’t asleep, he would gouge their eyes out. Horrifying stuff.”

Coppelius not only steals Olympia’s eyes in the opera, he tears her apart, but that is nothing compared to stealing people’s shadows.

The music is beautiful, Scott-Stoddart said. The famous barcarolle, a duet sung in a gondola in Venice by Giulietta and Niklausse, was never intended by Offenbach to be part of the original opera.

“But when it was being put together to be performed after Offenbach’s death, the composer doing the cutting and pasting (Ernest Guiraud) grabbed this duet to set up that act. Now even most revised versions leave it in, but it has nothing to do with Niklausse.”

Music director for Tale of Hoffmann is pianist Tara Scott.

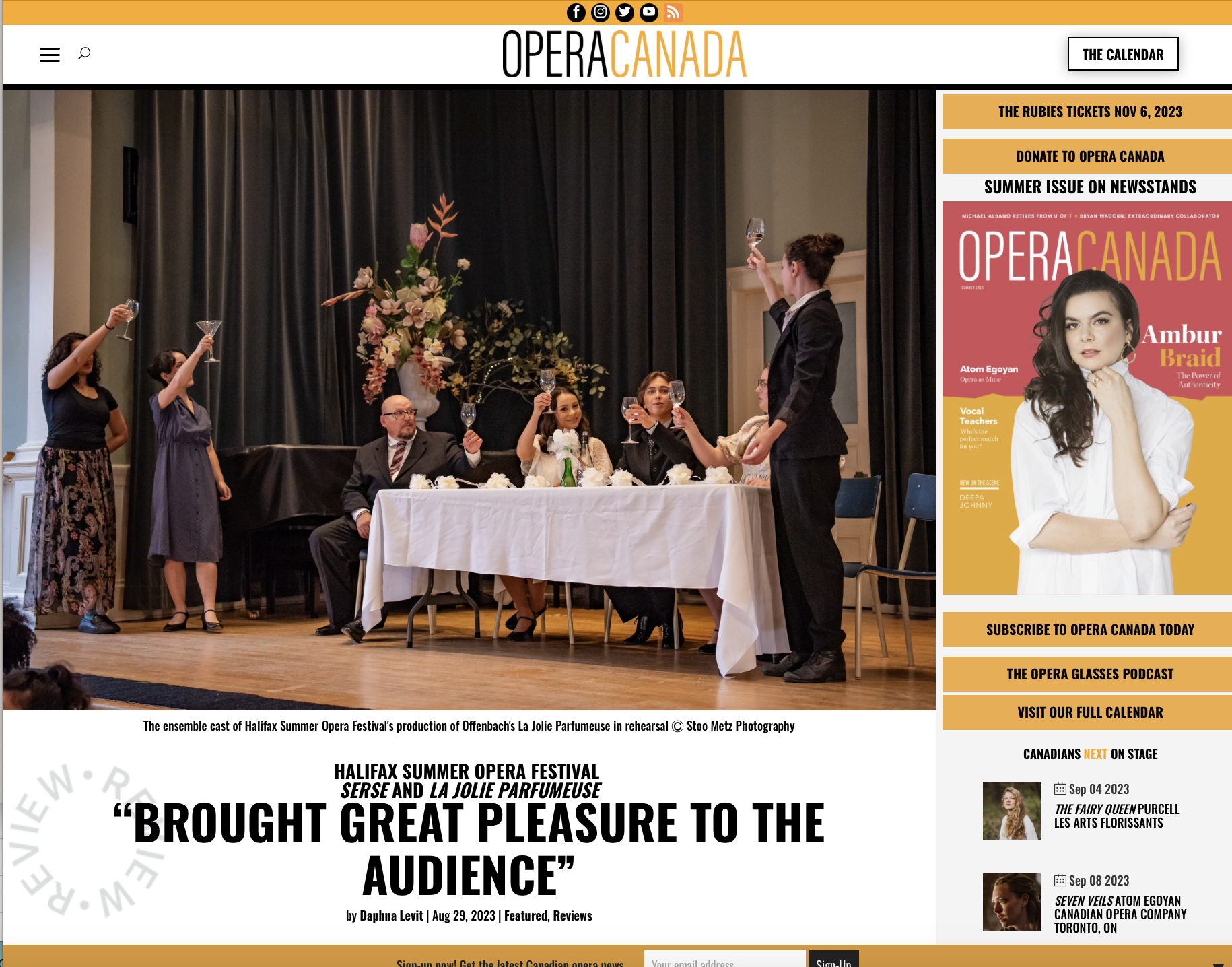

With 21 characters, the show has been double cast and roles distributed among 44 young singers from Canada, the U.S., and Korea who have been rehearsing in the workshop since July 1.

The workshop will also present Mozart’s well-loved singspiel, The Magic Flute. Directed for the stage by Garry Williams and David Mosey, who also translated the libretto, The Magic Flute music is directed by pianist Greg Myra.

“The music is gorgeous,” Scott-Stoddart said, “and the original story was a singspiel, intended as a popular entertainment. (The Magic) Flute is hard to direct because, on the one hand, it makes no sense . . . absolutely none. The directors have made some choices to point out . . . that the original opera is very misogynistic, which was typical of its time.”

The directors see the story of Tamino’s and Pamina’s love, Papageno’s ultimately successful search for a mate, and the testing of Tamino to see if he is worthy, all through the eyes of a child.

“She is telling this story to herself,” Scott-Stoddart said. “She is being used as a framing device for a story about a world where male and female are struggling, where there is a quest for virtue and beauty, and where there are monsters and wild animals and magic.”